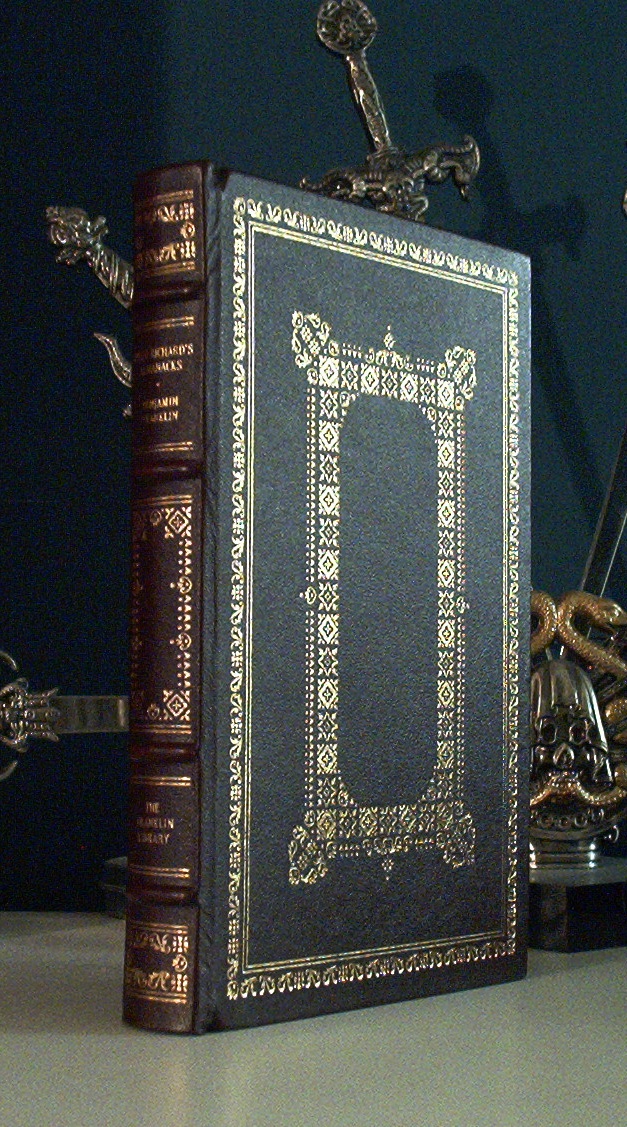

Easton Press Benjamin Franklin books

Poor Richard's Almanack - The Collector's Library of Famous Editions - 1983

Benjamin Franklin Biography - Ronald W. Clark - Library of Great Lives

Franklin Library Benjamin Franklin books

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin - 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature - 1983

Poor Richard's Almanack - 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature - 1984

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin - World's Best Loved Books - 1984

Benjamin Franklin biography

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) was an American printer, author, diplomat, philosopher, and scientist, born in Boston, Massachusetts His father Josiah Franklin, a tallow chandler by trade, had seventeen children; Benjamin Franklin was the fifteenth child and the tenth son. His Mother, Abiah Folger, was his father's second wife. The Franklin family was in modest circumstances. Like most of the New Englanders of the time. From his eighth to tenth year Benjamin Franklin attended grammar school, upon the completion of which he was taken into his father's business. Finding the work uncongenial, however, he entered the employ of a cutler. In his thirteenth year he was apprenticed to his brother James who had recently returned from England with a new printing press. Benjamin Franklin learned the printing trade, devoted his spare time to the advancement of his education. His reading included Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan, Plutarch's parallel lives, Daniel Defoe's Essay on Projects, Essays to Do God by Cotton Mather. Obtaining a copy of the third volume of the Spectator by Richard Steele and Joseph Addison, he set himself to master its prose style.

In 1721 James Franklin established the New England Courant, Benjamin Franklin, at the age of fifteen, was busily occupied in delivering the newspaper by day and in composing articles for it by night. These articles, published anonymously, won wide notice and acclaim for their pithy observations on the current scene. Because of its liberal bias, the New England Courant frequently incurred the displeasure of the colonial authorities. In 1722, in consequence of an article considered particularly offence, James Franklin was imprisoned for a month and forbidden to publish his paper, and for a while it appeared under Benjamin's name.

Not long afterward, however, as a result of disagreements with James, Benjamin Franklin left Boston and made his way to Philadelphia, arriving in October 1723. There he worked at his trade, and succeeded in making a number of friends, one of whom, Sir William Keith, the provincial governor of Pennsylvania, persuaded him to go to England to complete his training as a printer, and to purchase the equipment needed to start his own printing establishment in Philadelphia. Young Benjamin Franklin took his advice, and reached London in December, 1724. However, as he had not received from Keith certain promised letters of introduction and credit, he found himself, at eighteen, without means in a strange city. With characteristic resourcefulness, he obtained employment at two of the foremost printing houses in London, Palmer's and Watt's. His appearance, bearing, and accomplishments soon won him the recognition of a number of the most distinguished figures in the literary and publishing world.

Two years later, in October, 1726, Benjamin Franklin returned to Philadelphia, where he resumed his trade. The following year, with a number of his acquaintances, he organized a discussion group known as the "Junto", which later became the American Philosophical society. In September, 1729, at the age of twenty-three, he bought the Pennsylvania Gazette, a dull, poorly edited, weekly newspaper, which he made, by his witty style and judicious selection of news, both entertaining and informative. In 1730 Benjamin Franklin married Deborah Read, a Philadelphia girl whom he had known before his trip to England.

Henceforth, Benjamin Franklin engaged upon numerous public projects. In 1734 he founded what is generally considered to be the first public library in America, chartered in 1742 as the Philadelphia library. He first published Poor Richard's Almanac in 1732, under the pseudonym of Richard Saunders. This modest volume quickly gained a wide and appreciative audience, and is homespun, practical wisdom exerted a pervasive influence upon American character. In 1736 Benjamin Franklin became clerk of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, and the next year was appointed deputy postmaster of Philadelphia. About this time, he organized the city's first fire company and introduced methods for the improvement of street paving and lighting. An Academy, set up according to a plan submitted by Benjamin Franklin in 1734, later became the University of Pennsylvania. Always interested in scientific studies, he devised means to correct the excessive smoking of chimneys, and invented, around 1744, the Franklin Stove, a superior open stove which furnished greater heat with less fuel consumption.

In 1747 Benjamin Franklin began his electrical experiments with a simple apparatus which he received from Peter Collinson in England. He advanced a tenable theory of the leyden jar, supported the hypothesis that lightning is an electrical phenomenon, and proposed an effective method of demonstrating this fact. His plan was published in London and carried out in England and France before he himself performed his celebrated experiment with the kite in 1752. He invented the lightning rod, and offered what is called the "one-fluid" theory in explanation of the two kinds of electricity, positive and negative. In consequence of his impressive scientific accomplishments, Benjamin Franklin received honorary degrees from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and Oxford University in England. He also became a fellow of the Royal Society, and was awarded its Copley Medal for the year's most distinguished contribution to experimental science.

In 1748 Benjamin Franklin sold his printing business to his foreman. Daniel Hall. Two years later he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly, in which office he served until 1764. He was appointed deputy postmaster general for the colonies in 1753, and in 1754 he was the delegate from Pennsylvania to the intercolonial congress which met at Albany to consider methods of dealing with the threatened French and Indian War. Benjamin Franklin’s Albany plan, in many ways prophetic of the United States Constitution of 1787, provided for local independence within a framework of colonial union, but was too far in advance of public thinking to obtain ratification. It was Benjamin Franklin's stanch belief that the adoption of this plan would have averted the American Revolution.

When the French and Indian War broke out, Benjamin Franklin procured horses, wagons, and supplies for the British commander General Edward Braddock by pledging his own credit to the Pennsylvania farmers, who thereupon furnished the necessary equipment. However, the proprietors of Pennsylvania Colony, descendants of the Quaker leader William Penn, in conformity with their religious opposition to war, refused to allow their landholdings to be taxed for the prosecution of the war, and in 1757 Benjamin Franklin was sent to England by the Pennsylvania Assembly to petition the King for the right to levy taxes on proprietary lands. After the accomplishment of his mission, he remained in England for five years as the chief representative of the American colonies. During this period he made friends with many prominent Englishmen, including the scientist Joseph Priestly, the philosopher David Hume, and the political economist Adam Smith.

Benjamin Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1762, remaining until 1764, when he was once again dispatched to England as the agent of Pennsylvania. In 1766 he was interrogated before the House of Commons regarding the effects of the stamp act upon the colonies, and his testimony was largely influential in securing the repeal of the act. Soon, however, new plans for taxing the colonies were introduced in Parliament; Benjamin Franklin was increasingly divided between his devotion to his native land and his loyalty as a subject of the British crown. At length, in 1775, his powers of conciliation exhausted, he sorrowfully acknowledged the inevitability of war. Sailing for America after an absence of eleven years, he reached Philadelphia on May 5, 1775, to find that the opening engagements of the revolution, the battles of Lexington and Concord had already been fought. He was chosen a member of the Second Continental Congress, serving ten of its committees, and was made postmaster general, which office he held for one year.

In 1776, at the age of seventy, Benjamin Franklin made a journey to Montreal, suffering great hardship along the way, in a vain effort to enlist the co-operation and support of Canada in the War of Independence. Upon his return, he became one of the committee of five chosen to draft the Declaration of Independence. He was also one of the signers of that historic document, making before the assembly the characteristic statement "We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately". In September of the same year, he was chosen, with two other Americans, Arthur Lee and Silas Deane, to solicit economic assistance in France. His scientific reputation, his integrity of character, and his wit and gracious manner made him extremely popular in French political, literary, and social circles, and his wisdom and ingenuity secured for the United States aid and concessions which perhaps no other man could have obtained. Against the vigorous opposition of the French minister of finance, Jacques Necker, and despite the jealous antagonism of his coldly formal American colleagues, he managed to obtain liberal grants and loans from the French King Louis XVI. Benjamin Franklin encouraged and materially assisted American privateers operating against the British navy, especially John Paul Jones. On February 6, 1778, he negotiated the treaty of commerce and defensive alliance with France which represented, in effect, the turning point of the American Revolution. Seven months later, he was appointed by Congress the first minister plenipotentiary from the new nation to the court of France.

In 1781, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay were appointed to conclude a treaty of peace with Great Britain. The final treaty was signed at Versailles, France, on September 3, 1783. During the remainder of his stay in France, Benjamin Franklin was accorded honorary distinctions commensurate with his notable and diversified accomplishments. His scientific standing caused the French King to appoint him as one of the commissioners investigating the Austrian physician Franz Anton Mesmer and the phenomena of animal magnetism. As a high dignitary of one of the most distinguished Freemason Lodges in France, Benjamin Franklin had the opportunity of meeting and speaking with a number of the philosophers and leading figures of the French Revolution, upon whose political thinking he exerted a profound influence. Although he favored a liberalization of the French government, he opposed change through violent revolution.

In March, 1785, at the age of seventy-nine, Benjamin Franklin, on his own request, was permitted to resign his duties in France.

No sooner had he returned to Philadelphia, however, than he was chosen as president of the Pennsylvania executive council, which office he filled for a period of two years. In 1787 he was chosen a delegate to the Convention which drew up the Constitution of the United States. Benjamin Franklin was deeply interested in all philanthropic projects, and one of his last public acts was to sign a petition to Congress, on February 12, 1790, as president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, urging the abolition of slavery and the suppression of the slave trade. Two months later on April 17, he died in his Philadelphia home at the age of eighty-four.

Benjamin Franklin's notable service to his country was doubtless the result of his great skill in diplomacy. To his common sense, wisdom, wit, and industrial knowledge, he joined great firmness of purpose, a matchless tact, and a broad tolerance. Both as a brilliant conversationalist and a sympathetic listener, Benjamin Franklin had a wide and appreciative following in the intellectual salons of the day. His literary reputation rests chiefly on his unfinished autobiography, which is a true epitome of his life and character.

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

Written initially to guide his son, Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography is a lively, spellbinding account of his unique and eventful life, now a classic of world literature that is sure to inspire and delight readers everywhere.

Benjamin Franklin's autobiography is one of the greatest autobiographies of all time but it was incomplete. Franklin ended his life's story in 1757, when he was fifty–one. He lived another thirty–three eventful years, serving as America's advocate in London, Pennsylvania's representative in the Continental Congress, and America's wartime ambassador to France.

Few men could compare to Benjamin Franklin. Virtually self-taught, he excelled as an athlete, a man of letters, a printer, a scientist, a wit, an inventor, an editor, and a writer, and he was probably the most successful diplomat in American history. David Hume hailed him as the first great philosopher and great man of letters in the New World.

Benjamin Franklin - A Biography by Ronald William Clark

This fully documented account of 'the first American' gives a detailed and lively picture of the writer who invented the lightning conductor; the politician who spent years as emissary in London trying to prevent the American War of Independence; the statesman who, when war came, served as the United States representative in Paris, intriguing for French aid and American victory.

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life

Benjamin Franklin is the Founding Father who winks at us. An ambitious urban entrepreneur who rose up the social ladder, from leather-aproned shopkeeper to dining with kings, he seems made of flesh rather than of marble. In bestselling author Walter Isaacson's vivid and witty full-scale biography, we discover why Franklin seems to turn to us from history's stage with eyes that twinkle from behind his new-fangled spectacles. By bringing Franklin to life, Isaacson shows how he helped to define both his own time and ours.

He was, during his 84-year life, America's best scientist, inventor, diplomat, writer, and business strategist, and he was also one of its most practical—though not most profound—political thinkers. He proved by flying a kite that lightning was electricity, and he invented a rod to tame it. He sought practical ways to make stoves less smoky and commonwealths less corrupt. He organized neighborhood constabularies and international alliances, local lending libraries and national legislatures. He combined two types of lenses to create bifocals and two concepts of representation to foster the nation's federal compromise. He was the only man who shaped all the founding documents of America: the Albany Plan of Union, the Declaration of Independence, the treaty of alliance with France, the peace treaty with England, and the Constitution. And he helped invent America's unique style of homespun humor, democratic values, and philosophical pragmatism.

But the most interesting thing that Franklin invented, and continually reinvented, was himself. America's first great publicist, he was, in his life and in his writings, consciously trying to create a new American archetype. In the process, he carefully crafted his own persona, portrayed it in public, and polished it for posterity.

Through it all, he trusted the hearts and minds of his fellow "leather-aprons" more than he did those of any inbred elite. He saw middle-class values as a source of social strength, not as something to be derided. His guiding principle was a "dislike of everything that tended to debase the spirit of the common people." Few of his fellow founders felt this comfort with democracy so fully, and none so intuitively.

In this colorful and intimate narrative, Isaacson provides the full sweep of Franklin's amazing life, from his days as a runaway printer to his triumphs as a statesman, scientist, and Founding Father. He chronicles Franklin's tumultuous relationship with his illegitimate son and grandson, his practical marriage, and his flirtations with the ladies of Paris. He also shows how Franklin helped to create the American character and why he has a particular resonance in the twenty-first century.

Poor Richard's Almanacks

Poor Richard’s Almanack was a yearly almanac that was published by Benjamin Franklin under the pseudonym Richard Saunders. A popular pamphlet in colonial America, Poor Richard’s Almanack was filled with the wit and wisdom of Benjamin Franklin in the form of hundreds of proverbs and other data.

Benjamin Franklin's classic book is full of timeless, thought-provoking insights that are as valuable today as they were over two centuries ago. With more than 700 pithy proverbs, Franklin lays out the rules everyone should live by and offers advice on such subjects as money, friendship, marriage, ethics, and human nature. They range from the famous 147 A penny saved is a penny earned 148 to the lesser-known but equally practical 147 When the wine enters, out goes the truth. 148 Other truisms like 147 Fish and visitors stink after three days 148 combine sharp wit with wisdom.

Benjamin Franklin's classic Poor Richard's Almanac is chiefly remembered for being a repository of Franklin's aphorisms and proverbs, many of which live on in and are commonly used today, and have been newly typeset and included in this edition.

These maxims typically counsel thrift and courtesy, with a dash of cynicism.

The original Almanac also included the calendar, weather, poems, and astronomical and astrological information that a typical almanac of the period would contain and those sections are typically of little interest to the modern reader.

Comments

Post a Comment

Share your best book review and recommendation